The problems with Bridgerton

What a fictional Regency-inspired series can teach us about women and marriage, classism, and the dangers of gossip.

Warning! This post contains spoilers.

I recently just finished watching season four of Bridgerton.

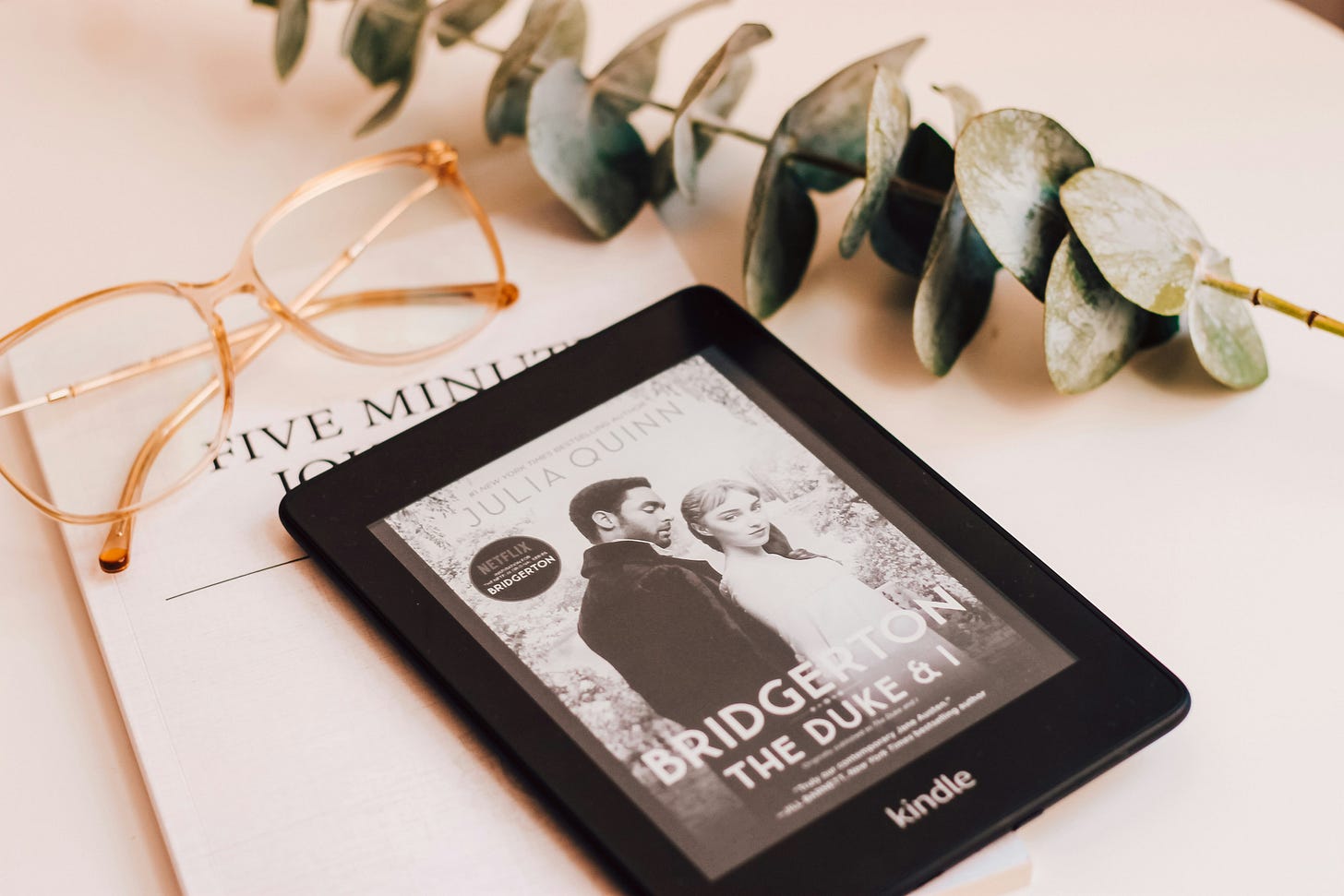

If you don’t know, the Netflix series is a Regency romance based on a series of novels of the same name by American author Julia Quinn. The books and show follow wealthy noble families, including the very popular and envied Bridgertons as each of their eight children come of age and look for a spouse.

The show is produced by Shonda Rhimes, an American TV producer and screenwriter, whose long line of television hits includes Grey’s Anatomy.

I never read or even heard of Quinn’s books before, but got sucked into Bridgerton during its first season, which aired in December 2020. That was several months into the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. We all needed something fun and colourful to watch on TV.

First of all, I want to point out what I enjoy about Bridgerton, including its diverse cast of incredibly good looking actors. I mean, is everyone on this show gorgeous?

I especially think the breathtakingly stunning Simone Ashley, who played Kate Sharma, and incredibly handsome Jonathan Bailey, who plays Anthony Bridgerton are just a fantastic on-screen match. I could feel the chemistry coming off the screen.

Besides, Kate rides horses, and she — or her stuntwoman — is the kind of rider I’d love to be. I love the scenes where there are horses.

Bridgerton is filled with passion, lust, and hot sex, which, besides its colourful and often over-the-top costumes, make it a hit. The series focuses on women’s desires and pleasure. I joked that women love it because the men in their own lives are boring (I said women love the gay hockey series and international hit Heated Rivalry for the same reason).

Bridgerton is also inspired by Jane Austen novels set in Regency-era England. It’s not historically accurate; the musical score includes orchestral versions of songs by Taylor Swift, Miley Cyrus, Coldplay, Olivia Rodrigo, and others, for example.

Still, I enjoy anything inspired by Austen’s work.

But like Austen’s works, Bridgerton offers its own lessons. I thought about those lessons today after rewatching season four last night. This is the season in which Benedict, the second eldest Bridgerton brother, looks for love.

I won’t get into all the details but I have a few thoughts on some of what we learn in Bridgerton. Stick with me!

Women and the “marriage market”

As I wrote, Bridgerton follows the love lives of each of the Bridgerton children. So far, Anthony, Daphne, Francesca, and Colin are married off.

In season four, Benedict tries to find his “woman in silver,” who he met at a masquerade ball. Eloise says she’s “on the shelf.” Meanwhile, Gregory and Hyacinth are too young for their debuts. Their seasons await.

There are plenty of other women in the show, too, including the many mistresses of the men. They include Siena Rosso, an opera singer, who is Anthony Bridgerton’s longtime love affair in season one. Many of the mistresses and the women working in brothels remain unnamed. They certainly aren’t the kind of women the Bridgertons or anyone in high society marry.

Meanwhile, the women who are on the marriage market are trained to be wives. They must be skilled in music, conservation, drawing, needlework, dancing, languages, and more, yet they have no agency. Their sole purpose is to get married, produce heirs, and look beautiful and poised while doing it.

It’s no wonder Eloise rejects all of this. So does Penelope Featherington, Eloise’s best friend, a wallflower who has no marriage prospects in the first two seasons of the show, despite her mother’s best intentions to push her into the marriage market.

Penelope has found another secret life: As Lady Whistledown, the author of a social pamphlet that captures the attention of “The Ton” (a term used to describe the English town and derived from a French term meaning “le bon ton” or good manners).

Penelope makes a fortune writing her social pamphlet that’s filled with bits of gossip she hears while standing against walls of ballrooms during high society parties. No one suspects that Penelope is Whistledown. No one notices Penelope at all, except to make fun of her (her tormentors include her mother and two sisters).

Penelope does have a longtime crush on Colin Bridgerton, but Colin puts Penelope into the “friend zone.” That’s before they share a passionate kiss in season three.

In Bridgerton, women are marriage material, mistresses, or spinsters. Their lives and security — or lack thereof — revolve around their relationship status. Has this changed all that much? Don’t we all sort of decide what women are marriage material or not?

Jane Austen wrote of women’s lives and their limited choices in Regency England. Austen herself never married and died at the age of 41. Her novels, however, remain widely popular and studied to this day. Last year was the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth. There were celebrations around the world.

Whether Austen knew the power of her pen we’ll never know, but she understood the roles of women in her time that still play out today.

Classism

Bridgerton focuses on the lives of the wealthy. None of the characters have jobs, but they have titles: Duke, duchess, viscount, viscountess, lord, lady, and so on.

Their jobs, as far as I can tell, involve going to lots of balls and parties, looking gorgeous, and trying to find spouses. The men have more fun being rakes on the side.

There’s an entire other set of cast members in the series: it’s the actors who play the servants. We really don’t get to know them well, except for Varley, the head maid of the Featherington household. I remember wondering about Varley’s backstory at the end of season three.

Well, much to my surprise, we get to know the servants more in season four. This season focuses on Benedict Bridgerton who meets a young woman in a silver dress at his mother’s masquerade ball.

Inspired by the classic Cinderella story, the young woman in silver, whose name is Sophie, is a maid in another household. Her evil stepmother made her a maid of the house but Sophie, with the help of her coworkers, goes to the ball in disguise.

She meets Benedict at the ball but just like Cinderella, she has to leave at midnight, leaving behind a long silk glove that Benedict holds onto as he searches The Ton to find her.

Bridgerton is not the first series to explore the lives of the servants of the upper class. That was the plot of the BBC show Upstairs Downstairs. Downton Abbey does the same.

We will get more of Varley’s story in part two of season four. We’ll also learn more about the other maids, too. Honestly, they’re the ones doing the real work.

Gossip

This really is the crux of the show, which is narrated by Lady Whistledown, who is voiced by Dame Julie Andrews.

By the end of season three, The Ton knows the identity of Whistledown when Penelope comes forward with her confession, thanks to a scheme by Queen Charlotte to uncover the town gossip.

Penelope said she wrote her gossip column because she was so fascinated by everyone in The Ton and the lives they led. Writing as Whistledown gave her power, she said, but she used that power in harmful ways.

Penelope asks for forgiveness and promises to wield her pen more responsibly. And she does.

In season four, Penelope writes about the ongoing “maid wars” in The Ton, as servants find new employment and demand better wages and treatment. I write about labour issues and I have to say I enjoyed this turn of events! Yeah, for the maids fighting back and demanding living wages!

Queen Charlotte, however, does not. The queen said she didn’t care for news on the maid wars, saying she didn’t even have maids (she has hundreds). Queen Charlotte wants the dirt on the love lives of her people.

Gossip may be information, as Penelope says, but it’s not the best way to wield a pen or tongue. We have all gossiped and been the target of gossip before, but as Bridgerton shows, gossiping has its price. Gossip is not always harmless and can, in fact, be abusive. It ruins lives and reputations, even in the fictional Ton where the Bridgertons live.

Penelope’s writings on the maid wars show the ways in which we can write as a way to punch up to power, to support the marginalized, and make a positive difference for society.

Wielding a pen responsibly means speaking to the front of someone, not behind their backs. Wielding a pen is an act of courage; gossip is the act of a coward.

I wouldn’t want to fit into high society in any era, but I love afternoon tea with its tiny, crustless sandwiches and other savory and sweet treats. I’d even have afternoon tea with Queen Charlotte of Bridgerton, but I’d have to warn her first that the only tea [gossip] that I like is Tetley.

As always, thanks for reading,

Suzanne

P.S. Apologies to fans of Bridgerton and Red Rose tea!

I love the way it has so many African and Asian people! It gives us a different view than that which European colonial history gave us. I love to see some neurodivergent and disabled people that would have in reality be hidden away.

The sets and costumes are so rich.

So much is not true to history but opens our imagination to alternatives.

This, AND all you wrote about.